- posts

Published on 07/03/2017

The necessity of redoing everything once again...

Image CopyrightDessin et Construction

CopyrightDessin et ConstructionThe architect's gestures are played out in the here and now – through the fog of received ideas, practical conventions and fashions – but they point away from the present. Our lines and words negotiate a future, and calibrate distances to multiple pasts. Lines, words, pixels, scraps of card or plastic: our tools are insubstantial, but they are all we have to steer a course between the rock of permanence and the currents of constant change.

For the most part we architects hold Time, and its attendant disorder, firmly in check – for example with the clean and vacant photographs we show each other of that brief instant when the builders have left and the users have yet to impose themselves. If there is one thing that can shake us out of this shallow present, it is taking a building designed for one reality and adapting it for another, completely different one. I am not talking here of work born of continuity and success – such as the growth of an institution or a business - but that born of failure, disruption and dissolution. The temporal nature of the architect's work is inseparable from the work of adaptation, demonstrating Viollet-le-Duc's dictum: “an architect can only form part of a whole; he begins what others will finish, or finishes what others have begun.” [1] Depending on your perspective, we don't even finish, completion is only ever provisional.

The buildings inherited from failure are like charred logs amongst the ashes, material traces of an immaterial energy that is now consumed. To rake through the embers is a sad, confusing business. The decline of Monceau Fontaine, of Royal Boch, of Interlait is traced on the pages of Le Soir: the fragile optimism of takeovers that briefly seemed to offer renewed competitiveness; the sluggish opportunism of investors and governments; dizzying volumes of production that nonetheless weren't enough. Each year a million and a half tonnes of coal, nine thousand tonnes of ceramics, four hundred and eighty million litres of milk: not enough. Not enough, it seems, to compete at a continental or global scale, but too much for a rapid transition to crafted, high added value production. Stripped of stock and plant, the balance sheets remain unresolved: sites equivalent in size to a small city, populated by a few non-ephemeral buildings; ground and water permeated by toxins accumulated over decades or centuries, pioneering vegetation building new ecosystems; the anger, solidarity and resolve of former employees, the curiosity of neighbours long kept at arm's length by the factory wall. In these discontinued but unfinished processes, matter and social energy are closely, almost inseparably entwined.

Remains of the coal mine, the ceramic works and the dairy are now shored up and fitted for new uses. At Le Martinet, one of fourteen pit-heads of the vast Monceau Fontaine coalfield, the conical slag heaps sprout with vigorous growth; at their foot the plain is punctuated by scattered pavilions of brick and concrete, repaired but yet to be occupied; at La Louvière, the three brick bottle kilns are all that remains of the vast ceramics works, enclosed by new museum spaces and surrounded by empty plots awaiting development; at Dison near Verviers, the core of the tall concrete dairy factory has been adapted to accommodate a supermarket, a café, a performance space, meeting rooms and a television studio.

These sites testify to the metamorphoses of the region: a fabric of interdependent industries woven over several centuries, torn and unravelled over a few decades, the aggregated companies now dissolved into scattered and unrelated works, repaired room by room, the soil cleaned one grain at a time. The same struggle, varying according to local circumstances, but in essence the same, is being carried out in the Black Country and north of England, in the north-east of France, in Germany's Ruhr. In this transition, even modest progress is hard won.

For such transformation is characterised by profound mismatches of scale. It is not just that our industrial regions are so large, and have so many installations which are now discontinued, which challenge the bearing capacity of our remaining economic activity. The mismatch of scale is of an existential nature. For these works are the residue of centuries in which matter and labour were mobilised on a mass scale; to tackle them under the conditions of an atomised society and economy is demanding in the extreme.

The project at le Martinet has been propelled by an unusual level of citizen mobilisation – can we see in this a residue of a collective spirit forged a thousand metres below? The residents of the neighbouring quarter have campaigned tirelessly, ever since the first threat back in 1976 to re-mine the slag-heaps. This small but motivated group has confronted corporations and cajoled public authorities, achieving protected environmental status for the richly wooded slag-heaps, advocating the acquisition of the site as a nature reserve in 1999. Since 2007 they have pushed ambitious plans for renewal focused on the environment, comprising city farms, a centre for the interpretation of nature, a training centre for environmental trades, new housing of high environmental performance: the gaps, between ambition and common practice, between demonstrable value and investment cost, are both rousing and unsettling.

At Dison, developer and commune held conflicting views, one advocating clearance, the other retention of the old factory. The heavily reinforced concrete structure carried high costs of demolition relative to the low land values of this economically marginal region.

As long as architects have been ed with the production of new buildings, they have operated in conditions of apparent certainty and control. Needs are crystallised in a defined building brief, means and ends calibrated through the budget, the tools and processes of the discipline are those refined over centuries of productive thinking, mobilising industrially produced materials into structures that submit their users to a kind of industrial discipline. This control is not ceded by todays architect-artist-shamans, fitting imagined needs to eye-catching structures – if anything their authority is elevated.

Projects such as Le Martinet and Dison confront the architect with radically different roles and challenges. Here, control and certainty have been absent. The architects have been called on, or have inserted themselves into the process, to nurture what social capital adheres to the mute material remains; to achieve sufficient social consensus and economic traction between divergent interests for a project to move forward; to manage a process of shrinkage and subdivision of the vast industrial footprints; to assimilate these enclaves and structures into the common currency of urban life. The exercise of judgement and the economical use of limited means are the last of the skills inherited from the industrial heyday of the discipline, leaving the architect more Odysseus than Prometheus: resourceful and improvisational, navigating an unfamiliar landscape and negotiating with its guardians.

As one commentator would have it, “Nothing much is left of the scenography of the modernist theory of action: no male hubris, no mastery, no appeal to the outside, no dream of expatriation in an outside space which would not require any life support of any sort, no nature, no grand gesture of radical departure —and yet still the necessity of redoing everything once again in a strange combination of conservation and innovation that is unprecedented in the short history of modernism.” [2]

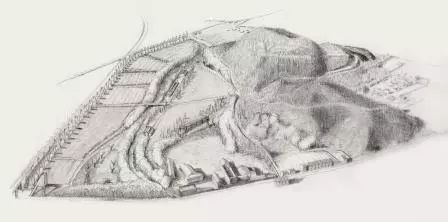

The operations led by the architects Dessin et Construction at le Martinet echo those of the old works: Triage et Lavage, sorting and cleaning. Between the foot of the slag-heaps and the abandoned, overgrown railway line, half a dozen deeply decayed structures have been demolished; the old changing rooms, a robust brick structure, has been simply restored, with new roofs and windows; its aerial bridge now connects to an absence; the engine house has been stabilised, its filigree concrete window frames repaired, but is left a ruin, open to the winds. Originally dwarfed by the winding gear and nestled behind storage buildings, it is now the focal structure of the plain beside the road, an emblematic structure at a beguilingly modest scale, making sense of the array of truncated girders and concrete pit-caps at its feet.

Deeper into the site, behind a retaining wall of crushed rocks in wire gabions, the black earth has been reclaimed by livid grasses and leaves, and by white blossom. The old locomotive hall, a fine structure of vaulted concrete, has been reroofed and reglazed; a skeletal steel shed on a central summit sits amongst a forest of slender white trunks; a series of concrete basins host standing water beside the wooded ponds of the old railway line; across a stabilised bridge, an area is undergoing exploratory cleansing by phytoremediation.

These works are a preparatory phase for localised future developments, yet also appear in limbo: the restored buildings lie unoccupied several years after completion. For the moment, the whole has stopped a long way short of the comité de quartier's ambitions, while the vacancy suggests it exceeds the commune's commitment. Despite this awkward triangulation, and the sheer disproportion between 27 hectares and the € 3.8 million available for this phase, the value of what has been done appears remarkable. Informed by years of listening, of careful observation, of delicately poised negotiation, the architects have made hundreds of judicious decisions across buildings and landscapes, with rigour and sensibility, but without sentiment. They have acted like the best of editors, reinforcing what is distinctive and durable, but creating space for chapters yet to be written. In doing so they have amplified the qualities of this hybrid landscape, where natural and man-made merge into one. The open engine house and shed are neither romantic relics nor assertive renewals, but feel rather like a statement of publicness: an invitation to occupy this machine in the garden, a gesture of incompletion and open-endedness.

At Dison, the architects Baumans Deffet have acted as brokers between partners who were initially reluctant, or were simply unable to see the possibilities. In the architects' own formulation, “the project is defined as the unifying element between the logics of market and non-market, in themselves contradictory… it is a translation of the democratic will to rebalance the synergies between the economic, social, environmental and cultural”.

The dairy was an aggregation of structures occupying a site 400 metres long, following the narrow valley at the heart of the town. The architects' work was to first of all to demonstrate the capacity of the site and concrete factory structure, both to the developer owner and to the commune. The public authorities were persuaded to take a financial stake in the project, unlocking the use of the tall upper floors for a range of community uses, from meeting rooms to a 150 seat theatre; the local television station was drawn into the mix. Removal of the lower outbuildings created space for a row of new retail units, while the ground floor of the old factory had the clear spans and height for two larger shops.

In these circumstances, design is a form of clear-eyed opportunism. The construction cost of around €1.150/m2 is a sign of the brutal effectiveness of the architects' tactics. They have utilised the existing capacity of the concrete frame to bear new insertions such as the soundproof studios. The muscular columns and their crude capitals are everywhere retained, including where structures have been removed; new external walls are in dark brick and profiled steel. The grand colonnade of industrial pillars and the facetted bulk of the factory shell are austere and impressive presences within the tight confines of the valley. The public interiors are necessarily opportunistic, too. Displaced from street level by higher value uses, the raised courtyard and roof terrace sit either side of the cultural centre foyer, offering a view of the wooded ridges defining the town, and a sense of release. As at le Martinet, the architects' work of division and opening is a decisive first step in re-assimilating the enclave and its raw shells into the habits and imaginations of citizens.

While the challenge of adaptive re-use takes us architects outside our professional comfort zone, and into unfamiliar new territories and roles, it also charges core concerns of the discipline with new tension. At both le Martinet and Dison the question of scale is at the heart of things: not scale in some abstract, compositional sense, nor in a vague humanistic perspective, but in the confrontation between an atomised society and the remains of a mobilised economy. The social construction of architectural scale is inseparable from the task. To even start to address the legacy of a mobilised economy has required the construction of alliances and the maintenance of collective energy, and the architect is deeply implicated in this action.

The fragile, improvised tools used by the architects of le Martinet and Dison illuminate this reflection. A drawing portrays the mine site with the dreamy detachment of a child, cool and harmonious but richly observed and slowly elaborated. A large model of white card portrays the dairy factory, cut about and added to, its vast halls occupied by gatherings of plastic figures. One wouldn't dare to present images so tentative or detached – in other words, so open to interpretation - in a design competition. In a competitive context, the winning imagery often serves to make the architecture complete and palpable: convincing but closed to participation. Yet the pencil drawing and the card model have offered the users something unfinished to complete in their imaginations, and have allowed the architects to make the strategic decisions without jumping to conclusions about detail.

Ours would be an exhausting and ruinous profession if every project required as intensive and lengthy negotiation as le Martinet and Dison. Yet their architects have found, in their role as editors and brokers, an unaccustomed closeness to the questions their society is grappling with. Unsheltered from social and economic currents, negotiating a link between mobilised past and granular future, they show us there is an unsuspected resourcefulness amongst our ranks, capable of navigating the treacherous currents of our time.

Written by Willian Mann within the framework of the publication Inventories#2 which completes the eponym exhibition.[1] Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire d'architecture, Relevés et observations par Philippe Boudon et Philippe Deshayes, Liège, 1979, p. 18.

[2] Bruno Latour, ‘A Cautious Prometheus? A Few Steps Toward a Philosophy of Design (With Special Attention to Peter Sloterdijk), accessed at http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/112-DESIGN-CORNWALL-GB.pdf

Image CopyrightDessin et Construction

CopyrightDessin et Construction

- actionsDate de l'événement

5/12/2024Published on 28/10/2024

-

A vos agendas ! Cities Connection Project #7 à Bruxelles

Nous avons le plaisir de vous convier au vernissage de l’exposition Cities Connection Project qui aura lieu le 5 décembre 2024 à 20h30 à la Faculté d [...]

- actionsDate de l'événement

20 - 30/11/2024Published on 28/10/2024

-

Inventaires#4 à Paris

Nous avons le plaisir de vous inviter à la présentation de l'ouvrage Architectures Wallonie-Bruxelles Inventaires #4, Vers une démarche architecturale [...]